Recently, I left my 11-year career as a high school Social Studies teacher to help my wife start up her new preschool. The above question has been frequently asked. Perhaps I'm wrong, but it feels like this question is loaded, like "Isn't this a big step backwards?"

Answer #1: I'm more of a part-time pre-school teacher.

I'm the school Manager (for lack of a better title). I love the change of "job" largely because it lets me do a variety of tasks on a daily basis: fix things up, sit on my couch with my laptop or participate in the classroom. I'm simultaneously HR department, accountant, building supervisor and, the subject of the question, the #1 substitute teacher.

Answer #2: I wouldn't have done this had I not already realized that, at its core, teaching is the same at all ages.

Rule 1 in any classroom environment is that the kids must feel safe, physically and mentally. During all of the fun parts of teaching, we have to remember that the biggest part, the base of Maslow's famous pyramid refers to physical well-being. For high-schoolers and preschoolers alike, they have to get enough sleep, eat well and feel appreciated before other lessons begin having an impact.

So many kids are so on the edge about this, and this is not just a poverty-related issue. Even well-to-do kids who seemingly have it all may be neglected by their parents: both parents work late, with an endless stream of cousins, baby-sitters and nannies spending more time with kids than mom and/or dad. Or, maybe mom and dad are home every night, but the kids are plopped in front of a TV or constantly play video games. (I recently saw a picture of a 2-year-old playing a war-simulation video game in the lap of a parent… ergh.) It's no surprise that school is often the warmest, safest, lovingest place for a child to be.

Answer #3: Montessori practices are completely in line with what I wanted to do in my high school classroom.

Answer #3: Montessori practices are completely in line with what I wanted to do in my high school classroom.

Answer #3: Montessori practices are completely in line with what I wanted to do in my high school classroom.

Answer #3: Montessori practices are completely in line with what I wanted to do in my high school classroom.

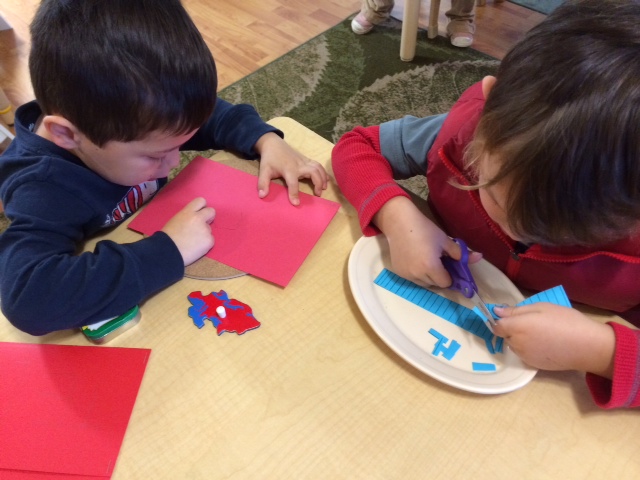

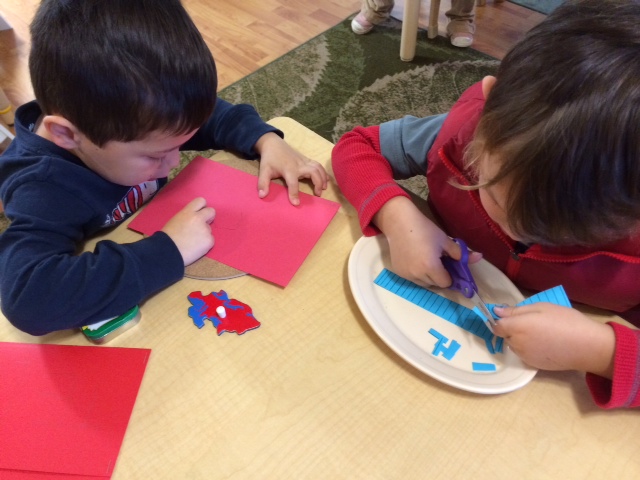

Very quickly after I met Lulu, I realized that what she was doing with preschoolers aligned perfectly what I was doing with high schoolers. Creating an open, safe classroom, teaching communication skills and letting students choose the way they work were all components of both of our classrooms. (I won't get into not being allowed to go further down that road. Not for today, at least.)

A couple of weeks ago, a UT professor came to visit the school, interesting in enrolling his son a year from now. I asked him what he already knew about Montessori. After a pause, he replied "Project-based learning." The answer took me by surprise, but it is spot-on.

In the larger picture, in which I truly believe that project-based learning is the future of education, a Montessori school ideally prepares young children for the choices, personal responsibility and interpersonal relations that will enable them to succeed working with others later in their educational and professional lives.

So, the final answer: I love being a part of this Montessori classroom, and I want to make it as good as it possibly can be.

A couple of weeks ago, a UT professor came to visit the school, interesting in enrolling his son a year from now. I asked him what he already knew about Montessori. After a pause, he replied "Project-based learning." The answer took me by surprise, but it is spot-on.

In the larger picture, in which I truly believe that project-based learning is the future of education, a Montessori school ideally prepares young children for the choices, personal responsibility and interpersonal relations that will enable them to succeed working with others later in their educational and professional lives.

So, the final answer: I love being a part of this Montessori classroom, and I want to make it as good as it possibly can be.